[Every once in a while I come across something Tekumelyáni that stretches my credibility a bit. Of course, it's fiction, so I don't worry too much. Still, I think it's helpful if I can find something in the real world that can lighten the burden on our disbelief suspenders. "High cartography objects" would be one of those things. --Talzhemir]

On Tékumel, "low" cartography is the use of flat maps. "High" cartography utilizes sculpted objects. Unreadable to the common person, they convey great meaning to those trained in the art. Since Tsolyáni people have paint and ink and scrolls, why would humans use esoteric three-dimensional items that take a great deal of effort to produce?

Let's look at a couple of real world parallels for insight. The closest thing to High Cartography is probably the travel carvings made and used by indigenous people of the Arctic Circle.

These three are Inuit reference tools that describe the coast of Greenland. They are made of wood. They show the fjords and the landforms visible from shore.

This information would remain valid for centuries. So, making a carving might be well worth the effort.

What are the advantages of this method over flat maps? First, they're for use at sea- markings on bark, parchment, and paper are less durable. Second, they were so far north that their world was plunged into twilight or night for months. There was very little light by which a map could be read.

In the South Seas, another tactile "map" device was the mattang. This is a generic "teaching" mattang. What it depicts is the crossing of wave fronts caused by the flow of water around an island.

Experienced sailors did not need to look to see them in the water. They could sense the wave direction and magnitude by paying attention to the canoe pitching beneath them. Even if they were far from sight of land, they could follow the wave fronts to find an island.

Here is an actual mattang of the Marshall Islands. It is made out of cowry shells, sea grass, and palm "twigs" from the center rib of a leaf). Called "rebbilib" there, these were still in use until about World War II.

Polynesians in their great canoes often slept through the heat of the day and rowed by night. They also caught seafood that rose to the surface at sunset and night. It was important to have reference that worked in darkness.

Mattangs are traditionally learned by touching the various components and gently tracing them. One ancient Polynesian belief was that there was a different repository for memories of this kind, "body memories". Today, we do know that some people are more effective at learning and memorizing if there is a kinetic or tactile component.

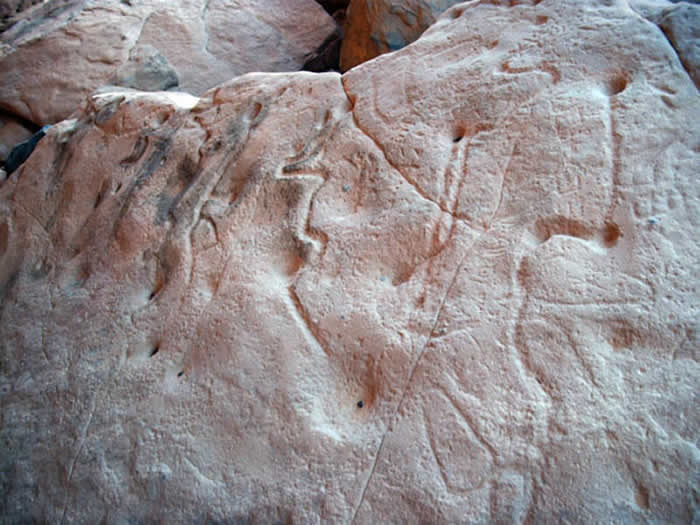

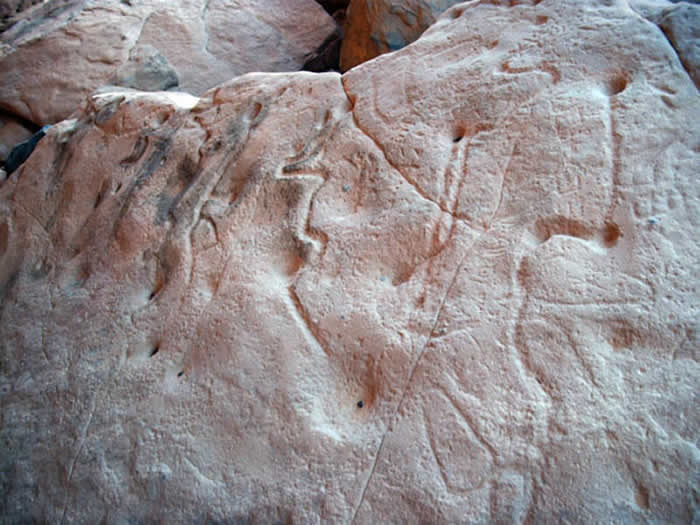

Inuit sticks and Polynesian mattangs are meant to be portable. This map is in Libya in a well-hidden location. We can infer that it was meant to be memorized because it is carved into the rock face.

The lines are wadis or valleys, and the holes are water wells. Probably engraved around 9000 years ago, it shows an area called Wadi Tashwinat. (Click here if you would like to see some of the rock art of Wadi Tashwinat! http://www.temehu.com/tashwinat.htm)

The map's location at Wadi Takdhalt hints that it was probably meant to be hidden. The surface is well-worn by touching. By not carrying a map object, the chances of an outsider learning of precious water resources was minimized. (The exact location of the map: N24 51.124 E10 31.143)

It's remarkable that the Wadi Tashwinat map has lasted so long. Wood, bone, paper and leather are devoured by mildew and beetles. Steel is extremely rare and copper turns to greenish black powder. Even glass just becomes a lump because it is a slow-moving liquid.

Given those alternatives, then, it makes sense that some scholars of Tékumel might prefer carven stone. They're aware that humanity has lost vast amounts of information. They want the fruits of their labor to last many millenia, and they do.

|

Author

Author

The Plausibility Department: "High Cartography"

The Plausibility Department: "High Cartography"